How to Self-Publish a Photo Book: Lessons from Belle-Île-en-Mer Workshop

The Second Birth of the Image: A Book-Making Odyssey from Cappadocia to Belle-Île em Mer Brittany in France

For a photographer, pressing the shutter is only half the act. The moment that image transforms into a memory, an object, a tangible “story,” is where the real magic begins. Today, I want to share the story behind my “Cappadocia” book from years ago, woven together with the technical and emotional notes on “autoedition” (self-publishing) that I refreshed during a recent workshop in Belle-Île-en-Mer.

This post is not just a memoir; it is a roadmap for my friends who dream of creating their own photography book.

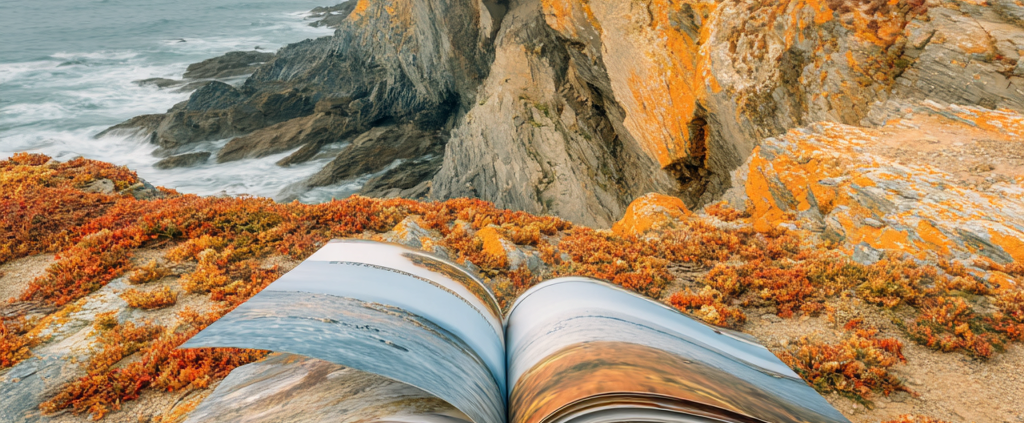

The Winds of Belle-Île and the Book as a “Reading Machine”

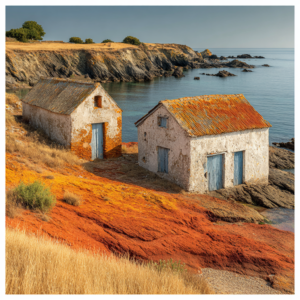

Last February, I found myself in Belle-Île-en-Mer. It is an island that changes its face several times a day—sometimes battered by rain, sometimes bathed in brilliant sunshine—testing one’s nerves just as much as one’s images. There were seven of us, hailing from Finland, Switzerland, Poland, France, and Turkey. We all shared a common desire: to transform our photos from mere portfolio files into an object that stands on its own—a form that is thought-out, constructed, and inhabited.

Here, under the guidance of the internationally renowned photographer Claudine Doury and the master book designer Caroline Lusseaux, I was reminded of a crucial truth: Making a book is not just “printing”; it is a craft in itself.

It is often assumed that a good photo book depends solely on good photos. This is true, but insufficient. As Caroline emphasized at the workshop, a book is actually a “rhythm machine” (machine à rythme). It is the rhythm of the pages, the rhythm of the white spaces (the “rests”), the rhythm of visual echoes, and most importantly, the rhythm of the hand turning the pages.

The Spark of Inspiration: From Cambodia to Cappadocia

Returning to the journey of my own “Cappadocia” book; the project actually began far away, among the Angkor temples of Cambodia. I was captivated when I saw “Elegy,” a book by John McDermott, who had left his life in England to dedicate 14 years to that land. At that moment, the fate of my Cappadocia archive, which I had been accumulating for 10 years, changed. I told myself, “I must do a great work like this. I must carry the mystery of Cappadocia to the world”.

I had made amateur attempts before, such as “Ripple Marks” and “Doğa” (Nature), but this time had to be different. It had to be a true art book.

The 4 Pillars of a Good Book and the “Team” Spirit

Whether in the training at Belle-Île or during my Cappadocia process, the greatest truth I have observed is this: You cannot do this alone. For the Cappadocia book, I brought together four “indispensable” factors:

1. The Curator: A ruthless and professional eye for selection. Famous photographer Fethi İzan undertook this task for my book.

2. The Designer: The visual identity of the book. The esteemed Mehmet Ali Türkmen even designed a special logo for the project.

3. The Printer: Perhaps the most critical stage. Without the gentle touch of A4 Ofset and my dear friend Alparslan Baloğlu, who specializes in photo book printing, we could not have achieved that quality.

4. The Writer/Critic: Text that breathes soul into the book. Orhan Alptürk, whom we sadly lost in 2022, added intellectual depth with his introduction.

This team worked in an atmosphere of perfect cooperation and brotherhood. When doing your own book (autoedition), you must either wear these four hats yourself or find the right partners. Remember, your printer is not a service provider, but a partner who saves you from mistakes.

Constructing the Visual Story: “Every Choice is a Renunciation”

For the Cappadocia project, I had 24,000 frames accumulated over 15 years—ranging from analog to digital, black and white to color. How does a “story” emerge from such chaos?

This is where the lesson of “Editing” from Belle-Île comes into play. Selecting is hard, but ordering them is harder. Two images side-by-side must create an invisible third image—a tension, a question.

In Cappadocia, we made a decision: We eliminated the people, the tourists, and the dining venues. We told a nature story starting from the majesty of Mount Erciyes and descending into the texture of the tuff. We selected only 119 photos out of 24,000. Because every choice is indeed a renunciation. A book is not an archive; it is a proposition.

Technical Integrity: The Memory of Paper and the Art of Printing

One of the topics we discussed emphatically at Belle-Île was paper selection. Paper is not a neutral surface; it is the “skin of the image”. It determines contrast, the depth of blacks, and even the speed of reading.

In my Cappadocia book, we had to unite photos taken with different techniques (film, slide, digital) under a common language. For this, we used a tritone printing technique, likely a first in Turkey. By printing with tones of “Burnt Sienna” (terre de sienne brûlée) on paper imported from Italy, we achieved that mystic unity.

For those attempting autoedition, here is some golden technical advice:

• InDesign is a Discipline: Bleeds (fond perdu), margins, and templates do not accept errors. Strictly follow your printer’s specs (usually 3mm or 5mm bleeds).

• The Double-Page Rule: A book is read in “spreads” (openings), not single photos. Do not place two “dominant” photos facing each other where they cannibalize one another. Sometimes a white space, a “rest,” allows the viewer to breathe.

• Prototype It: The image on the screen is deceptive. You must make a physical dummy. You can only understand where the story drags or flows when you turn the pages with your own hand.

A Practical Checklist for Autoedition

Distilled from my Belle-Île notes, here is a short guide that should be on your desk while making your book:

1. Define the Promise: Before starting, write a single sentence: “This book is about …, showing …, to make one feel …” If you can’t write this, the reader won’t understand it either.

2. The Rhythm Test: Does the book “hold up” during a 3-minute fast flip? Does it bore you during a 30-minute slow read?.

3. Text Usage: Do not use text as an “explanation” or an “apology” for the photos. Text is there to orient the reading.

4. Binding (Reliure): Even the most beautiful design is wasted if the book doesn’t open properly. Binding is the architecture of the book.

Final Word: Does a Project End?

The answer to the frequently asked question, “Does a project ever end?” is clear to me: Yes, it must. A work that never ends is not a project. The Cappadocia book is finished; the Turkish and English editions sold out and became rare items. Now, it lives its own life.

When photography transforms into a book, it accepts being “transformed.” This is not a betrayal, but the image’s second birth. If you have a long-term, fragile project that is valuable to you, do not be afraid to embody it in book form. Assemble the perfect team (or acquire those skills), feel the smell of the paper, finish your project, and set sail for new horizons.

Life is a collection of successive projects.

Stay with love.

Ps: Some technical aspects;

Mehmet Ömür